What Sarawak’s Orang Ulu reminded the Queen

Published on: Sunday, March 17, 2024

By: David CC Lim

Text Size:

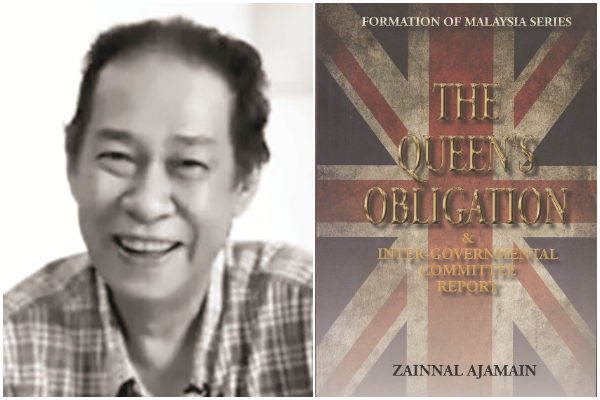

'The leaders and Elites of the Federation of Malaya may do so with impunity to the eleven states but they cannot touch the Borneo states however hard they try to change the Federal Constitution – they cannot change the Inter-Governmental Committee Report or the Malaysia Agreement, 1963.' – Late Zainnal Ajamain. (Pic on the right: The Queen’s Obligation book)

The promise had been made in response to a letter to the Queen from the Orang Ulu of the Baram river basin expressing concern about their future. The letter was passed to the District Officer, Baram, Ian Urquarhat, who remembers as follows:

“When Sarawak became a Colony, a promise had been made that the Crown would not hand over the country to anyone else without the consent of the people. When I was District Officer, Baram, I was startled when representatives of the Orang Ulu presented me with a letter, which they asked me to pass to Her Majesty the Queen.

The letter reminding the Queen of her promise, said that they heard that discussions were taking place about Sarawak’s future and demanded that no action should be taken without their consent.” (Sarawak Anecdotes, A Personal Memoir of Service 1947 – 1965, copyright, Ian Urquhart, 2015)

Zainnal Ajamain, the author and self-publisher of The Queen’s Obligation (Zainnal Ajamain, Kota Kinabalu, copyright, 2015), then embarked on a book sale cum lecture promotion in the main towns of Sabah and Sarawak.

A Sabahan from Kota Kinabalu, Zainnal was an economist, having graduated with a Master’s degree from the University of East Anglia, England.

Zainnal’s purpose in writing the book was, as he says is to promote the importance of Malaysian history and the issues that really matter – Sabah and Sarawak rights.

It is his contention that the leaders of the two Borneo territories had for decades either failed or neglected to avail their states of those rights and safeguards under M63, and that this had caused the watering down and erosion of those rights, as a result of which the two states have fallen behind West Malaysia in social and economic development.

In Sarawak a similar concern about the state’s plight was raised when a group of people formed a party called, “Sarawak Association for Peoples’ Aspiration” (SAPA) to highlight the neglect by their state leaders of the rights under MA63. Their aspiration was and still is for the autonomy and the eventual independence of Sarawak.

Their argument was that there was no consensus from the people to merge their home territory with Malaya and Singapore; further, that Britain had failed to honour its promise to the Sarawak people.

Consequently, a memorandum was submitted Sarawak Government calling for the opening of negotiations with the Federal Government for a referendum on Sarawak independence on September, 16, 2021.

“The Queen’s Obligation” (TQO) on the other hand accepts the merger with Malaya and Singapore in 1963 as fait accompli, and sees a benign intention behind the British plan in integrating the Borneo territories with Singapore and Malaya, as the title suggests.

According to Zainnal, the fate of the two territories and Malaysia was already determined by mid-1962 at the meeting at Chequers between British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan and the Tunku on July 28, 1962.

In a letter addressed to the Tunku on the same day, Macmillan laid out the “Chequers Formula” that provided for the transfer of sovereignty over the two territories on August 31, 1963, “after consultation with the legislatures of North Borneo and Sarawak, and provision of safeguards for their special interests”. (TQO, p. 82).

Ghazali Shafie, Permanent Secretary of the Malayan Ministry of External Affairs and a key lieutenant of the Tunku, in his “Memoir on the Formation of Malaysia” (Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 1998 ) describes the meeting as follows:

“It was for me a great privilege to have witnessed on July 31,1962 such a historic and momentous occasion and be a party actively contributing in the preparations, deliberations and negotiations which gave birth to a new and proud independent nation.” (Ghazali Shafie’s Memoir on the Formation of Malaysia, Ghazali Shafie, Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 2004, p.261)

Earlier the Joint Public Statement issued by the British and Malayan governments at the conclusion of the Cobbold Commission survey on August 1, 1961, states, among other things, that the two governments had agreed “in principle” that “the proposed Federation of Malaysia should be brought into being by 31st August, 1963”.

The timeline of events thus far accorded with the agreement made between Macmillan and the Tunku as far back as July, 1961, that “Greater Malaysia” comprising Malaya, the two Borneo territories and Singapore would be formed by 1963.

Ghazali Shafie (left) admits Governor Goode telling him Stephens (right) was not in step with his own people in suggesting independence in 1963.

So effectively the fate of the two territories was thus signed, sealed and delivered, without their knowledge or consent of the people at the grassroots level of either territory.

It remained only for the two governments in the plot to agree on what rights and safeguards to grant to them, with the Tunku having the right of the veto over the British as subsequent events would show.

Be that as it may, Zainnal goes on to argue that although the British knew of “Kuala Lumpur’s colonial design” they had only limited means to protect the Borneo territories from Kuala Lumpur, pressed as they were with the apparent threat of the left wing elements winning support in Singapore, and with the geopolitical pressure, particularly from the United States to de-colonize.

Zainnal accordingly chose to cast a tolerant eye on the actions of the British government:

“There was however, nothing to stop them [the British] from inserting and constructing safeguards into the Constitutions (sic) of the Federation of Malaya. The amended Constitution was not to fulfill the need of a ready-made nation but it is a recipe for nation building – Malaysia was a state within a nation.”(TQO, p.170).

The last part about Malaysia being a “state within a nation” sounds enigmatic, but Zainnal explains:

“The leaders and Elites of the Federation of Malaya may do so with impunity to the eleven states but they cannot touch the Borneo states however hard they try to change the Federal Constitution – they cannot change the Inter-Governmental Committee Report or the Malaysia Agreement, 1963.”(ibid).

That is a powerful statement, which can be said to be the central message of the book that is directed at the leaders of the two territories.

In short, the leaders of the two territories have to know the rights and safeguards under MA63 to do justice to their people. Moreover, what has been legislated in the Federal Parliament that is detrimental to the interests of the two states of East Malaysia, can and should be repealed.

Unfortunately, members of Parliament (MPs) from Sabah and Sarawak whether through ignorance, complacency, sheer neglect or some equally odd reasons had supported Federal legislations that adversely affect the rights and safeguards of their home states.

Zainnal cites the amendment on July 28, 1976, to Article 1 (2) of the Malaysian Constitution as having the effect of lowering the status of the two states to the status of the states in pre-independent Malaya. The amended Article reads as follows:

“The States of the Federation shall be Johore, Kedah, Kelantan, Malacca, Negri Sembilan, Pahang, Perak, Perlis, Sabah, Sarawak, Selangor and Trengganu.”

The original provision for the “name, states and territories of the Federation” stated in the Malaysia Act, (no. 26 of 1963) states as follows:

“(1) The Federation shall be known, in Malay and in English, by the name Malaysia.

(2) The states of the Federation shall be

(a) The States of Malaya, namely, Johore, Kedah, Kelantan, Malacca, Negri Sembilan, Pahang, Penang, Perak, Perlis, Selangor and Trengganu, and

(b) the Borneo States, namely, Sabah and Sarawak; and

(c) the State of Singapore.

(3) The territories of each of the States mention in Caluse (2) are the territories comprised therein immediately before Malaysia Day.”

It is therefore disingenuous to argue that the amendment sought to “clean up” the Article with the separation of Singapore from the Federation when the net effect of the amendment was to put the two Borneo states on equal footing with the states of Malaya.

As Zainnal puts it, “it can also be construed as subordinating the Borneo States [to Federal authority].”

Zainnal further argues, the Malaysia Agreement, 1963 is in fact, a “Trust Deed” and therefore incontrovertible : “The lawmaker can change the Federal Constitution many times over, without the ability to change the “Trust Deed” all these changes mean nothing because these changes may not be “in the spirit and letter of the Agreement”.

The Malaysia Agreement appears deceptively simple, consisting of eleven articles on three pages, but hidden as it were under Article VIII, are the safeguards and the rights of the Borneo states, which after incorporation into the Constitution of Malaysia, according to A.J. Stockwell, Editor of the “British Documents on End of Empire: Malaysia’, constitute “an elaborated set of contracts concluded after prolonged and elaborate multi-lateral negotiation.”(TQO p.171)

Dr Michael Leigh the Australian political scientist (“The Rising Moon, Political Change in Sarawak”) observes that the Malaysia Agreement is not only valid, but is “a powerful, internationally registered agreement binding on the federal and the two state governments” in terms of the recommendation of the IGC beyond that which is expressed in the Malaysian constitution’.

Pointing to the text of the Agreement, in particular, Article VIII, which includes all the “assurances, undertakings and recommendations contained in the IGC report”, he says “the Article forms the legal basis for those who argue that Sarawak and Sabah have rights that are above and beyond those that apply to all the other states of present day Malaysia” (Deals Datus and Dayaks, Sarawak and Brunei in the Making of Malaysia” (Strategic Information and Research Development, 2018, p.46.)

At the negotiations over those rights, the British administrators who made up the majority of the members from the two territories in the Inter-Governmental Committee, tried to protect their interests from Kuala Lumpur.

These officials, however, had been put in the unenviable position of having on the one hand to listen to their superiors in Whitehall and compromise with the Malayans, and on the other hand to discharge their obligations to their subjects, the local Borneo population. Some of them had tried to reach out to the native population regardless, but the result was confusion.

One educated Iban member of the Sarawak National Party (SNAP), Charles Inka, thought that the native leaders were confused with the advice from the colonial officers:

“Some of the British officials advised one thing, some advised another. And our local people with diverse personal interests, were pushed in different directions…” (Tun Jugah of Sarawak, Colonialism and Iban Response, Vincent H. Sutlive Jr., Sarawak Literary Society, 1992.)

Zainnal describes these officers as “the second type, who were working and living in the Borneo territories, love Borneo and empathized with the people…” One such officer was undoubtedly, William Goode, then Governor of North Borneo. Goode had wanted the British Governors to remain for a number of years after Malaysia, but he was rebuffed by Razak:

“When we met, there was no progress with regard to the role of the Governors. Razak was quite annoyed with Goode who insisted that without the Governors the people might refuse Malaysia. Razak curtly interjected by saying that in that case the British could keep the two territories.” (Ghazali, Memoir on the Formation of Malaysia, Penerbit University Kebangsaan Malaysia, p.259, 1998).

Also, after the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association in Jesselton in August, 1961, and after being elected as chairman of the newly formed “Malaysia Solidarity Consultative Council (MSCC), Donald Stephens, leader of the United Naional Kadazan Organization (UNKO) was taken to task by the Governor, for his statement that the target date for Malaysia was 1963. Goode said that Stephens was not in step with his own people. (Ghazali Shafie, Memoir, p.73)

The retention of the Governors to oversee the internal administration in the Borneo territories for a transitional period of 3 to 7 years was one of the recommendations of the British members of the Inter-Governmental Committee.

The Tunku, however, would have none of it, and threatened to withdraw from the negotiations if the recommendation was in the report. Thus the condition was quietly dropped:

“The Tunku instructed Ghazali Shafie and Wong Pow Nee to withdraw from the Commission if that recommendation was to be in the final report. Any right for a state to later secede was [also] expeditiously ruled out, with little or no British objection.”(“Deals, Datus and Dayaks, Sarwak and Brunei in the Making of Malaysia”, p.21)

In view of the foregoing, it is debatable whether Zainnal’s rather reconciliatory attitude towards the British action in pushing the two states into the federation could be justified.

True, the British Prime Minister had insisted that the views of the Borneo people towards the Greater Malaysia proposal be sought against the Tunku’s wish to make that a fait accompli if he agreed to Singapore’s entry.

However, given the time frame allowed to elicit the views and feelings of the diverse populations of the two big Borneo territories, Macmillan’s stand seemed to be transparently perfunctory.

Even Lee Kuan Yew of Singapore had commented:

“But the Tunku had his price for taking in Singapore…[As far back as August (1961)]..The British deduced that since they needed the Malayan government to take over Singapore to keep the communist in order, he, the Tunku, would require that the Borneo territories should be completely integrated into the Federation first….The Tunku wanted Malaysia by August, 1962” (Lee Kuan Yew, The Singapore Story, Times Limited Editions, 1998, p.404, 416)

It should be noted that the community leaders of the two territories had publicly expressed their opposition to the scheme, but to no avail. The Sarawak United Peoples’ Party and the United National Kadazan Organization (UNKO) issued a joint statement to that effect in response to the Tunku’s call on July 18, 1961:

“Nearly all leaders in Borneo are agreed that first things must come first and the first thing which needed attention was a getting together of the Borneo territories; that when we talk with Malaya it will be as equals, not as vassals.

“If we join Malaya now the people who will come and take most of the top jobs will be from Malaya; Malayans who instead of being our brothers and fellow citizens will in fact be viewed, as they have been in Brunei, as the “New Expatriates....We feel that Malaya itself is trying to intrude and make us so dependent on Malaya that we would never really be able to obtain merdeka for ourselves.” ( quoted in The Straits Times, 18 July 1961, p. 8).

Donald Stephens, editor of North Borneo News, himself often seen as a pro-British leader, expressed his distrust of the scheme in strong terms:

“It would indeed be convenient for the British. They keep their base in Singapore – this would of course be one of the conditions for their signing over the Borneo territories. They improve their cordial relations with Malaya and everybody would be happy, except we, poor cousins, the wild men of Borneo, who would be the only ones left extremely unhappy because we would have been made just so many pawns in the game of power and politics in this region.”(Donald Stephens, quoted in The Straits Times, 11th August, 1961.)

Stephens, however, after the meeting of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) said that he himself had not made up his mind as to the best form Malaysia should take, insisting that the two territories should at least have obtained self-government first.

The MSCC met four times between August, 1961 and February, 1962, to discuss the terms of the merger. At the conclusion of the final meeting on February 3, the Council issued a ‘memorandum for Malaysia’ approving unanimously the plan proposed by the Tunku in May, 1961.

The formation of the MSCC marked a change in the sentiment of the local leaders of Sabah and Sarawak – except for SUPP which wanted independence first - towards the formation of Malaysia.

MORE NEXT WEEK

- The views expressed here are the views of the writer and do not necessarily reflect those of the Daily Express.

- If you have something to share, write to us at: [email protected]

ADVERTISEMENT